Female Genital Mutilation

- Home

- Female Genital Mutilation

Wassu Gambia Kafo

Female Genital Mutilation

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is a harmful traditional practice with strong and ancient sociocultural roots. According to the World Health Organization, it includes those procedures that, intentionally and for non-medical reasons, alter or injure the female genital organs. Internationally recognized as an extreme violation of human rights, FGM perpetuates gender inequality and discrimination, seriously affecting the health and well-being of women and girls. UNFPA estimates that more than 200 million women and girls alive today have experienced this practice and around 68 million girls face FGM by 2030 if we do not accelerate our efforts to abandon it.

Why is it practiced?

FGM is an extremely complex, sensitive and politicized issue, difficult to understand solely through normative definitions, classifications and/or geographical delimitations. It is necessary to have an anthropological view of the phenomenon to obtain an understanding of its significance that allows the subject to be approached with knowledge and respect. FGM has great symbolic meaning for the communities that practice it. In Africa, it is linked to two basic values of culture: the feeling of belonging to the community and complementarity between the sexes. In some societies, the practice continues to be part of initiation ceremonies into adulthood, directly influencing the construction of women's roles and status, granting ethnic and gender identity. It transmits a feeling of pride and belonging to the group, and becomes the physical proof that guarantees the femininity and virginity of the girl and the obtaining of the necessary knowledge to be able to belong to the community and the secret world of women (Kaplan, 1998; Kaplan, et al., 2013a). When the reasons for continuing with the practice are investigated, various reasons appear:

- “Tradition says so”: in order to guarantee that girls are prepared for adult life and for marriage, without being excluded from the community, families continue to practice this practice as a tradition that is sometimes lived as a rite of passage organized by mothers and grandmothers.

- “Religion says so”: FGM is practiced in Muslim, Coptic Christian and Falasha Jewish communities (in Egypt and Ethiopia, for example). Ignorance of its origins has led to its link with religion, although it is not mentioned neither in The Bible nor in The Koran.

- “It's cleaner”: Some practicing communities perceive women's external genitalia as body parts that are “dirty” before they are circumcised.

- “It is more beautiful”: the female external genitalia are considered to be “unsightly” parts, and in some communities, it is believed that the clitoris could reach the dimensions of the penis if it is not excised.

- “Preserves virginity, the honor of the family and prevents promiscuity”: in some societies, female virginity is a prerequisite and indispensable for contracting marriage on which the honor of the family depends.

- “Increases fertility and enhances fecundity”: Some communities believe that, if the baby touches the mother's clitoris with its head at the time of birth, it can cause death (mortality in primigravidas) or can cause physical or mental deformities.

Where is it practiced?

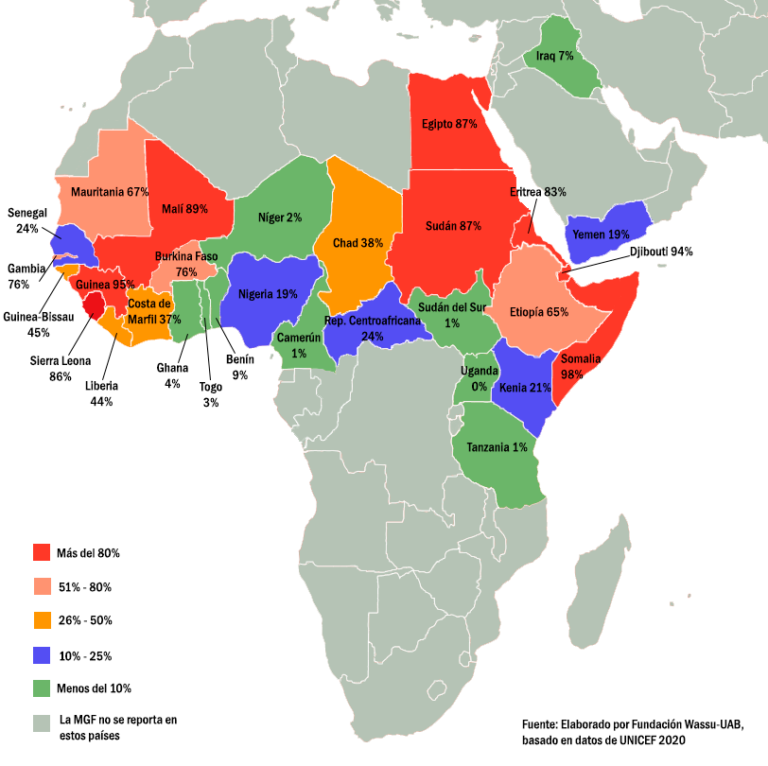

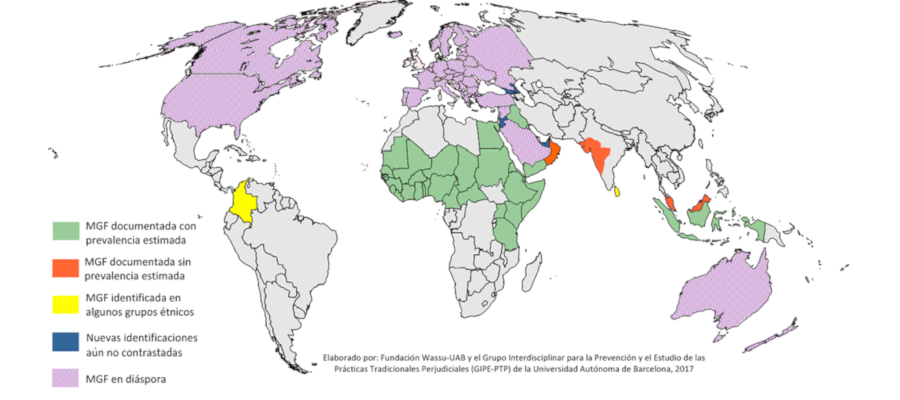

FGM is mainly practiced in 30 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as in parts of the Middle East and Asia (Yemen, Oman, northern Iraq, certain regions of India, Malaysia and Indonesia, among others).

However, due to migratory flows, what was once local is now global: FGM survives in diaspora and can be found in Europe, Australia, the United States of America, etc. Wherever migrants take their culture with them.

Types of FGM

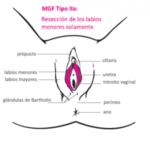

The World Health Organization classifies FGM into four types, based on its anatomical extent and severity: Image source: WHO, 2018.

Type I: partial or total resection of the clitoris and/or foreskin (clitoridectomy)

Type II: partial or total resection of the clitoris and labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (excision)

Type III: Narrowing of the vaginal opening to create a seal by cutting and repositioning the labia minora or majora, with or without resection of the clitoris (infibulation)

Type IV: all other procedures injurious to the external genitalia for non-medical purposes, such as piercing, incising, scraping or cauterizing the area